</img>

</img>

Implemented by Jordan Mecom and Alice Wang.

View the repository here.

This project implements the paper '’Video Textures’’ by Schodl, Szeliski, Salesin, and Essa. The aim is to create a ‘‘new type of medium’’ called a video texture, which is ‘‘somewhere between a photograph and a video’’. The idea is to input a video which has some repeated motion (the texture), such as a flag waving, rain, or a candle flame. The output is a new video that infinitely extends the original video in a seameless way. In practice, the output isn’t really infinte, but is instead looped using a video player and is sufficiently long as to appear to never repeat.

We’ll describe the algorithm in detail, and then share results and failure cases.

Approach and Algorithm Analysis

There are two main parts to the algorithm. First, the video texture must be extracted from the input video. Second, a new video that synthesizes the video texture must be created.

But, the key idea behind the algorithm is this: given a frame of a video, we can select a plausible next frame by randomly picking a similar frame to the one that would have been played in the original video. This next frame may not be the actual next frame in the input, but it may be. In this way, we can infinitely and smoothly extend a video.

Extracting the video texture

To extract the video texture, we need to compute how similar pairs of frames are to each other. This can be accomplished by calculating the sum of squared difference between each pair of frames, and storing the results in a distance matrix, D. From there, we can compute a probability matrix, P, which assigns probabilities between pairs of frames. P can then be used to calculate the next frame in the output video given a current frame: since a frame is a row, we discretely sample the next frame using the probability distribution across a row of P. The pseudocode is below

# Construct D, the distance matrix

D = pairwise distance between all frames, using SSD

shift D to the right by 1, to align the next frame with potential new frames

# Construct P, the probability matrix

sigma = average of non-zero D values * SIGMA_MULTIPLE

P = exp(-D / sigma)

normalize P so that the sum of a row is 1P is created using an exponential function and dividing by a constant, sigma. The paper notes that sigma is (often, but in our case always) set to a small multiple of the average non-zero D values. The user-set parameter SIGMA_MULTIPLE controls sigma further: smaller values of sigma force the best transitions to be taken, and larger values allow for more randomness. We typically set SIGMA_MULTIPLE to 0.05.

Preserving dynamics

In some cases, the input video has a fluid motion that the video texture should preserve. The paper gives the example of a pendulum swinging: the algorithm described above doesn’t account for the fact that original video has a side-to-side motion. So, the resulting texture may jitter back and forth since there’s no distinction that the next frame may have come from the left side or the right side in the original video.

This is easily fixed by modifying D so that the pairwise distance between frames also considers a few frames around it. This can be achieved by filtering D using a length 2 or 4 filter with weights set to the binomial coefficients (to approximate a Gaussian distribution, with the correct width). The psuedocode for this modification is below

# Modify D to preserve motion

w = a 2 or 4 length filter with binomial weights

w = diag(w) # Neighbors are on the diagonal in D

filter D with w

crop D along the edges due to the filter

# From here, continue on with making P as described aboveThe impact on D can be visualized below:

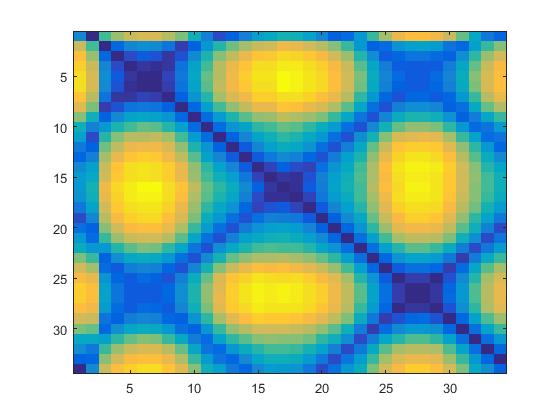

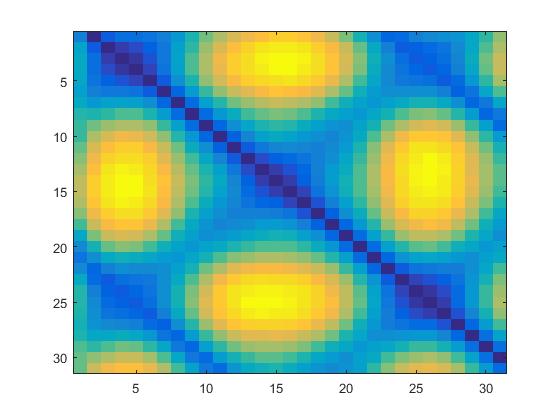

| Regular | Preserved motion |

|---|---|

|

|

Blurring can be observed along the diagonals, and D is slightly smaller in overall size due to the cropping.

Writing the video

Once appropriate transitions have been identified, we can then write the video texture out. The paper describes two approaches to do so: random playback, and video loops.

Random playback

Random playback is an easy to implement, intuitive, and fast approach. The algorithm is described in pseudocode below

start at some frame

repeat:

write the current frame i

discretely sample the next frame, j, using the probability distribution

found in P at the ith rowVideo loops

The motivation behind video loops is to preselect a sequence of loops that can be repeated, so that the resulting texture smoothly repeats when played on a conventional video player’s repeat setting. We attempted to implement video loops, but were unable to produce any compelling results with the algorithm.

The paper gives an example to describe how the video loops dynamic programming algorithm and scheduling algorithm works. Our implementation was successful on this example, but when we tested on real videos there were very obvious skips (see failure cases below) that shouldn’t occur.

We feel that the most likely cause of the problem was our selection of primitive loops. We pruned the input video as the paper describes, but there isn’t much discussion by the authors on how to actually select the primitive loops to run the video loop algorithm on.

Results

The results of the algorithm are displayed below, as looping GIFs. In all of the below examples we use random playback.

</img>

</img>

Above, we first demonstrate the primary example in the paper of a pendulum swinging. Here we’ve implemented random playback and did not preserve dynamics. As such, the resulting video skips unnaturally. This is solved in the next example by preserving motion.

</img>

</img>

The result is much better after using the filter as described above.

</img>

</img>

Snowfall makes for a great video texture as it’s very hard to perceive where the loop happens. Snowflakes all pretty much look the same, so the frame transitions are very smooth. Furthermore, the snow is falling quickly which makes it harder to notice any poorer transitions that may be made.

</img>

</img>

The waterfall performs slightly worse, although still does quite well. There’s a slight skip in the middle of the texture, but it’s only very noticable if you’re carefully looking. The paper mentions that this can be solved using cross-fading, but we didn’t implement this. In this case in particular, we believe cross-fading would work very well since water doesn’t have a sharp edges that would cause the fade stand out.

</img>

</img>

This is the first of four city video textures that we made. This one is the most interesting; because the input video is a time-lapse, the lighting across the scene changes noticably. The actual video texture algorithm performs well, however some pre-processing could improve it. For example, one could normalize the intensities of the frames of the input video to make the changes in the lighting less drastic.

</img>

</img>

When we first were introduced to the idea of video textures, we immediately thought of cinemagraphs which are ‘‘high quality gifs that are very smoothly looped’’. Although different in approach, (cinemagraphs are manually made and don’t require well defined patterns), the two ideas can produce similar results. We wanted to create a cinemagraph-style video texture, and so this was our attempt.

</img>

</img>

</img>

</img>

When the input video is well filmed, and lends itself to a nice video texture, the result can be very compelling. This is shown by the final two results, above.

Failure cases

But, not every input video worked out well. These cases are discussed in this section.

</img>

</img>

The texture above was generated by our video loops algorithm. Skipping is very noticable, when it shouldn’t be. Similar behavior was observed for every texture created by our video loops code.

</img>

</img>

This texture tries to preserve motion, but causes large hangs in doing so. We thought we could improve the waterfall result by preserving motion, but instead the quality actually degraded. We think that motion should only be preserved when there’s a clear movement pattern, such as the clock pendulum.

</img>

</img>

We thought the bear would slowly move around in the output video texture, but the result is much more jittery than expected. Perhaps a longer input video with more possible frames to choose from could create a better result. As the input video currently stands, there isn’t enough of a ‘‘pattern’’ to create a good video texture.